How Liars Jail the Innocent

State laws have no standards on police informants, whose wrongful testimony can put innocent people behind bars.

Sam Hadaway stands on a Milwaukee overpass near where the body of Jessica Payne, 16, was discovered in 1995. Hadaway says he was pressured by police to plead to a lesser crime and falsely implicate Chaunte Ott in the teenager’s murder. Ott was later exonerated by DNA evidence. Hadaway is now filing a motion to undo his felony conviction. Mario Koran/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

In his third round of questioning, Sammy Hadaway confessed.

After being held in a Milwaukee jail for several days in 1995, he told detectives that he saw his friend, Chaunte Ott, rape and murder a 16-year-old runaway named Jessica Payne.

Hadaway — who has cerebral palsy, epilepsy and brain damage and is referred to in medical records as a “poor historian” — said he robbed Payne before Ott raped and killed her.

The biggest problem with the confession: It was all a lie, one Hadaway now says he told police to avoid a homicide conviction that could have landed him behind bars for the rest of his life.

Based largely on Hadaway’s testimony — and that of another informant who avoided prosecution — a jury convicted Ott in 1996 of first-degree intentional homicide. He was sentenced to life in prison. As part of a deal, Hadaway pleaded guilty to robbery and received a five-year prison sentence.

“This case was essentially a case where it appeared to be going nowhere and the detectives in this case built this case out of absolutely nothing,” Mark Williams, a Milwaukee County assistant district attorney, said at trial. “They deserve the credit of the community for the job that they did.”

It was a case made through incentivized testimony, proffered by informants who had something to gain by cooperating with police.

Such individuals, often labeled “snitches,” are seen by many criminal justice experts as a weak link in the justice system — and as a leading source of wrongful convictions.

‘Inviting wrongful convictions’

Wisconsin has no specific policies regarding the use of informant testimony, which worries some state and national criminal justice experts.

“A state that has no protections against witnesses who are compensated for their testimony is inviting wrongful convictions,” says Alexandra Natapoff, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles and author of an award-winning book on the dangers of criminal informant testimony.

“A state that has no protections against witnesses who are compensated for their testimony is inviting wrongful convictions,” says Alexandra Natapoff, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles and author of an award-winning book on the dangers of criminal informant testimony.

Natapoff counts at least 10 other states that have taken steps toward regulating informant testimony or requiring that a person cannot be convicted based on the testimony of an accomplice unless that testimony is corroborated by other evidence.

The alternative, Natapoff says, is that more innocent people will be ensnared by police and prosecutors.

“We are beyond the day when we can close our eyes to the injustices and wrongful convictions that flow from incentivized witnesses,” she says.

Four years after Ott was convicted, attorneys at the Wisconsin Innocence Project began working on his case. The Innocence Project, a University of Wisconsin Law School program that investigates allegations of wrongful convictions, called for DNA testing of the semen collected from Payne’s body.

The DNA evidence, which excluded both Ott and Hadaway as possible contributors, matched a convicted serial killer named Walter Ellis who strangled and killed at least seven women between 1986 and 2007.

Two of Ellis’ victims were found in the same neighborhood where Payne’s body was discovered — one of them just a few houses away. Ellis, who will remain in prison for the rest of his life, has never been charged in Payne’s killing.

Ott was released in 2009 after serving more than 12 years in prison. A year later, the state Claims Board agreed to pay Ott $25,000, the maximum allowance for persons wrongfully convicted in Wisconsin.

Hadaway’s conviction, however, stands. With help from the Innocence Project, he is filing a motion to effectively undo his felony conviction.

Natapoff says that while some cases illuminate a single issue, Hadaway’s story runs the gamut of problems that stem from the use of incentivized witnesses.

“It includes a lying snitch, law enforcement that didn’t test DNA evidence and a false confession by a psychologically vulnerable individual,” Natapoff says. “It sums it all up in one terrible bundle.”

A staple of law enforcement

According to a 2005 report by Northwestern University Law School’s Center on Wrongful Convictions, a group of attorneys and advocates, the use of informants in criminal cases “probably arrived in the New World with the Pilgrims.”

In fact, the nation’s first documented wrongful conviction involved a “snitch.”

In 1819, brothers Jesse and Stephen Boorn were sentenced to death after a jailhouse informant claimed Jesse confessed to killing his brother-in-law. For his testimony, the informant was freed. The Boorns were spared when the brother-in-law turned up alive in New Jersey.

“Perjury or false accusations” were a factor in 17 out of 31 exonerations in Wisconsin since 1989, according to The National Registry of Exonerations, a joint project of the University of Michigan Law School and the Northwestern Center on Wrongful Convictions.

Natapoff, who is also a former assistant federal public defender in Baltimore, says criminal informants who are compensated for their cooperation can be used at every stage — from investigation to arrest to trial — and in almost any criminal case.

“It’s really become a staple of how American law enforcement handles cases,” she says.

Criminal informants can be direct participants, or witnesses to the crime. Others may be used by police in ongoing investigations — for instance, by wearing a wire while making a controlled drug purchase.

“We’ve seen that using these criminal informants is the single largest source of error in U.S. capital cases,” Natapoff says. “There are a lot of people sitting on death row who were convicted based on snitch testimony.”

The Center on Wrongful Convictions says incentivized witnesses were a factor in 45 percent of wrongful convictions in death penalty cases nationwide between 1973 and 2005.

Wisconsin Department of Justice spokeswoman Dana Brueck says the DOJ does not track how often criminal informants are used at trial, nor how often their testimonies are a determining factor in criminal convictions.

Natapoff says such a lack of data is typical nationwide: “Nobody really knows the extent of the problem because the government doesn’t keep track, and we don’t require them to.”

Most of the time, Natapoff says, cases involving informants are settled without a case going to trial. And that makes it harder to gauge the scope of the problem.

“Snitching is one of the most secretive aspects of the criminal justice system,” she says. “There are no incentives for anybody to come forward with details — not the practitioners such as prosecutors or detectives, and not those who cooperate in exchange for their testimony.”

‘Doing more good than it is harm’

Rick Coad, a Madison-based criminal defense attorney with experience in federal court, says informant testimony often involves people who are desperate enough to lie.

“You have these people that would do anything to save their own hide,” he says. “You can understand why they would provide false information.”

Coad says criminal informants have “become a pillar of drug cases.” Their testimony is used not only to determine culpability, but also to determine the weight of drugs that were allegedly sold — which can determine the length of the sentence.

“Good luck disproving these statements,” he says. “Unless the judge thinks he’s lying, you’re stuck with it. When you have these statements from somebody that knows about the case, but they’re not supported by evidence, it’s very difficult to disprove the testimony. It’s proving a negative.”

Lt. Brian Ackeret of the Madison Police Department says police get useful information from a variety of sources, ranging from concerned family members to confidential informants to people in jail seeking leniency from the justice system.

“There’s absolutely value in interviewing people who are involved in criminal activity,” Ackeret says. “There is value and greater good in trying to solve additional crimes. This is with an understanding that we need to assess their credibility, their motivations, and verify the information from multiple sources.”

Ackeret bristles at the word “snitch,” saying the term adds to the subculture that makes people reluctant to provide authorities with information. He says that while investigators have no authority to make promises, they can approach prosecutors to let them know witnesses have cooperated, which can weigh in their favor.

“Do we need to recognize that there are potential problems with confidential informant testimony?” Ackeret asks. “Yes, but I’d say overall the system is doing more good than it is harm.”

Indeed, jailhouse informant testimony can be used to catch criminals, sometimes preemptively.

In July 2012, several inmates at Grant County jail came forward with information that Robert J. VanNatta, 45, was offering a truck, a four-wheeler and a lawnmower in exchange for killing his estranged wife to keep her from testifying against him.

VanNatta was eventually convicted of resisting or obstructing a police officer in connection to the case.

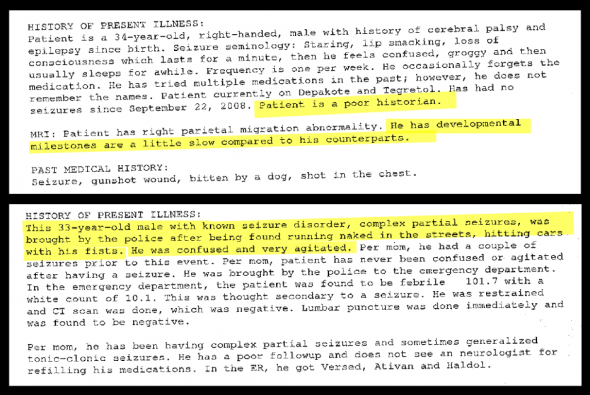

‘Patient is a poor historian’

Excerpts from Sam Hadaway’s medical records in 2008 and 2009. Click image to enlarge.

Innocence Project attorneys say that Hadaway’s intellectual disabilities call into question the validity of his testimony, and that the pressures of interrogation caused a psychologically vulnerable individual to confess to a crime he did not commit.

There is no evidence that Hadaway was evaluated by a psychiatrist before he testified against Ott, but medical records from 2009 tell the story of an individual with notable physical and intellectual limitations.

Hadaway has had cerebral palsy, and has suffered seizures since birth, the records indicate. He forgets to take his anti-seizure medication, he smacks his lips, he loses consciousness for minutes at a time, then awakes feeling groggy and confused — so confused he once ran through the streets naked, pounding on cars with his fists.

His “developmental milestones are a little slow compared to his counterparts,” according to medical records compiled at Froedtert Hospital in Milwaukee. “Patient is a poor historian.”

Dr. Bruce Hermann, a professor in the Department of Neurology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says that epilepsy and cerebral palsy affect different people in different ways, but for some individuals with chronic epilepsy, their intellectual capacity can worsen over time.

In general, he says, “the earlier the onset, the more likely the epilepsy is to have an effect on intelligence and cognition.”

In Brandon Garrett’s book, “Convicting the Innocent: Where Criminal Prosecutions Go Wrong,” he studied the first 250 people exonerated by DNA tests, taking a close look at the cases in which innocent people had falsely confessed.

Garrett, a law professor at the University of Virginia, says juveniles and individuals who have cognitive impairments are especially vulnerable to false confessions. In the cases he examined, 17 exonerees who falsely confessed had mentally disabilities or mental illnesses, and 13 were juveniles.

“All of those individuals would have been more suggestible and vulnerable to police pressure to confess – and to confess in detail,” he said in an interview.

He added that all but two of the 40 false confessions were reported to have included “inside information,” or details that only the true culprit could have known. The false confessions were so seemingly persuasive and detailed that judges repeatedly upheld them during years of appeals.

His findings also illuminate cases involving incentivized testimony.

More than 20 percent of the DNA exonerees had informants in their cases, including jailhouse informants, and also co-defendants. These informants routinely denied at trial that they had entered into any arrangement for leniency with prosecutors, but sometimes it emerged years later that they had.

“And almost without exception, these jailhouse informants claimed that these people had confessed to specific details about the crime,” Garrett says. “Now with the benefit of DNA testing, we know that they were lying and these innocent people could not have known those details.”

In some cases, multiple innocent defendants implicated each other and confessed, including cases where confessions were made by juveniles or individuals with mental disabilities.

This includes the famous Illinois Ford Heights Four case, in which two innocent men were sentenced to die and two others received lengthy sentences. Paula Gray, a 17-year-old informant who was mentally disabled, later recanted, saying she was fed information by police.

The case, which resulted in a $36 million lawsuit against the state of Illinois, fueled then-Republican Gov. George Ryan’s decision in 2000 to place a moratorium on executions until the state’s handling of death-penalty cases could be studied.

The Ford Heights Four ruling also helped lead to the institution of a “pretrial reliability hearing,” which is a formal procedure used in Illinois death-penalty cases to weigh the credibility of an informant before his or her testimony is heard before the court.

In March 2011, Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn abolished the death penalty and commuted the sentences of all 15 men remaining on that state’s death row.

Breaking points

Dr. Robert Galatzer-Levy, a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences at the University of Chicago, says that even for a person of average intelligence it can be extremely difficult to withstand police pressure.

Galatzer-Levy, who has given expert testimony in criminal trials as a forensic psychiatrist, says an interrogator uses the first 10 minutes of an interview to determine whether a suspect is guilty.

If police assume the person committed the crime, they use carefully designed interrogation techniques to confuse subjects, and convince them that it would be in his or her best interest to confess, he says.

“Imagine yourself terrified, with two police officers, very forcefully asking questions. Telling you that they know that you’re guilty. Also being told that there’s very little time,” Galatzer-Levy says. “Most ordinary people will break under that.”

“Now imagine that if you’re not all that bright or quick — these same techniques become incredibly powerful. A person with a mental limitation will have a hell of time doing anything other than what the police want them to, which is to confess.”

Garrett says that evidence shows that in some ways innocent people can actually be more likely to confess.

“There is an assumption that they can clear it all up later. They trust the system. They think, ‘I’ll get a lawyer, and we’ll clear this all up,’ ” Garrett says. “What they don’t realize is that once they sign a confession, it becomes almost impossible to undo.”

Legacy of regret

In April, Hadaway stood on an overpass near where, he was told, authorities discovered Jessica Payne’s body.

Like so many men who have been released from prison, he returned to a life framed by poverty. With every job application he submits, he is haunted by his felony conviction.

After his release, he says he worked temporarily in Milwaukee for a church, Holy Redeemer, and then at a Walgreens. He is now unemployed, surviving on food stamps and Social Security checks.

He hopes the motion his attorneys will file on his behalf will erase his felony conviction and make it easier for him to find work and improve his life.

But the odds are against him. Both Hadaway’s attorneys and Garrett recognize that reversing a conviction is incredibly difficult.

The standard of proof needed to reverse a conviction is much higher than what was needed to secure the original conviction, Garrett says, and in most cases, judges are very skeptical about new evidence such as recantations.

“It’s common to be mistrustful of informants. Judges and prosecutors assume that if a person lied once to benefit himself, he’s likely to do it again. His credibility is damaged,” Garrett says.

Hadaway has paid a heavy price for his actions. Around his neighborhood, he is known as a snitch, and he says people who know about the case want nothing to do with him.

He regrets testifying against his former friend Ott, but understands why people in such situations lie to authorities in order to help themselves.

“To be free,” he says. “To be out. There’s a lot of people in jail for something they didn’t do but somebody else said they did.”

Hadaway has not spoken to Ott since he testified against him, but said he was happy when he heard his former friend was exonerated.

If he were to see Ott on the street, there is one thing he would like to say.

“I’m sorry,” Hadaway says tearfully. “I’d tell him I’m sorry.”

Reporter Mario Koran wrote this story while working as a paid reporting intern for the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. For six months he also worked with the Wisconsin Innocence Project, where he received academic credits for helping to investigate cases and research criminal informant testimony.

The Center collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

-

Legislators Agree on Postpartum Medicaid Expansion

Jan 22nd, 2025 by Hallie Claflin

Jan 22nd, 2025 by Hallie Claflin

-

Inferior Care Feared As Counties Privatize Nursing Homes

Dec 15th, 2024 by Addie Costello

Dec 15th, 2024 by Addie Costello

-

Wisconsin Lacks Clear System for Tracking Police Caught Lying

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck